Bad clocks block FX best-ex

To get a good deal in fast-moving FX markets, buy-side firms need to know the time. Some of them don’t

Need to know

- Showing best execution in foreign exchange trades – and ensuring fair treatment – can mean tracking events at a sub-second level.

- Some buy-side firms struggle with this. One problem is order-management systems that round timestamps to the nearest second.

- “If an asset manager doesn’t know when a transaction took place on their behalf in the market, then that gap can be costly,” says Andy Woolmer of New Change FX.

- Another problem is the use of incorrect timestamps – there are 26 different stamps available in standard Fix messaging.

- The co-chair of the Fix community’s global technical committee floats the idea of an industrywide effort to standardise the treatment of timestamps.

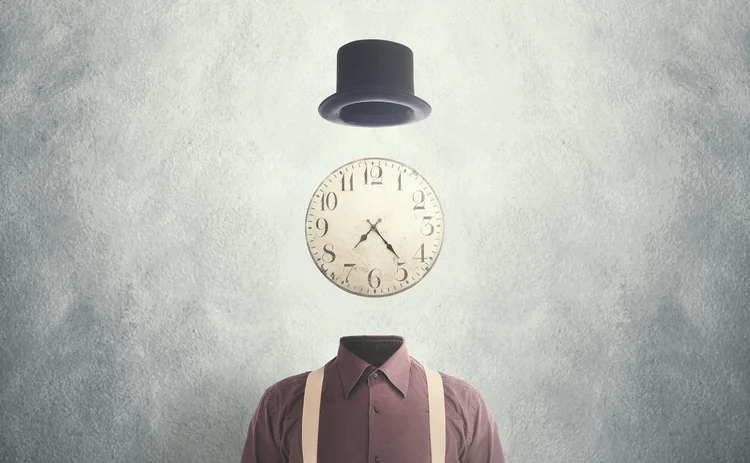

Flavor Flav, the hype man for hip-hop superstars Public Enemy, famously wore a large clock around his neck, so he knew what time it was.

He would not have been a success in modern foreign exchange markets, where participants increasingly need to care not just about hours, minutes and seconds, but also milliseconds and even microseconds. Unfortunately, in the form of clunky order-management systems (OMSs), observers claim some buy-side firms are still using the equivalent of Flav’s clock.

“We often see trade data coming from the OMS that only captures, for whatever reason, one-second intervals in its timestamps. There are 1,000 milliseconds in a second. A lot happens in a millisecond,” says Andy Woolmer, chief executive of New Change FX, a provider of transaction cost analysis (TCA).

A more insidious problem is the use of the wrong timestamps, of which there are 26 in the market’s standard messaging protocol, Fix – each one capturing a different, tiny event in the life of a trade.

These dual dangers of OMSs that only recognise yawning epochs and misunderstood stamps mean some investors still don’t know what time it is. That makes it difficult or impossible to be certain they are getting a good outcome, and being treated fairly, when trading.

Ensuring best execution is a regulatory requirement for asset managers under Europe’s second Markets in Financial Instruments Directive. Within FX, it applies to over-the-counter derivatives as well as for foreign exchange services that are ancillary to trades in assets covered by Mifid II best execution rules. That means best execution rules also apply for an FX spot provided for a client in connection with a derivatives order.

Stephan von Massenbach, director of FX consultant Modular FX Services, says buy-side firms should measure time precisely to avoid being taken advantage of: “A lot of FX market activity happens at the market microstructure level, which is measured in milliseconds. Clients need to ensure they have access to trade and market data with a time resolution suitable for analysis of execution quality.”

A brief history of timestamps

An OMS – such as BlackRock’s Aladdin or Bloomberg’s Asset & Investment Manager – is an internal system that connects portfolio managers with a firm’s traders. Traditionally, those traders will rely on a separate bit of kit, the execution management system (EMSs), to connect with venues and counterparties, and actually send orders to the outside world.

For regulatory reporting purposes, venues are mandated by Mifid II to record trades to the millisecond or better. Participants in those venues have their own granularity obligations, which depend on the type of activity they engage in – for voice and request-for-quote trading that is common in fixed-income markets, timestamps should be a second or better, while high-frequency algorithmic trading has to be reported in microseconds. Everything else is held to a millisecond standard.

Popular OMSs and EMSs match their timestamps to these obligations. When a trade passes through Bloomberg’s AIM, for example, timestamps are captured in seconds. It can then be routed on to Bloomberg’s accompanying equity or fixed-income EMSs – which are understood to capture timestamps at the granularity required by Mifid II. This is likely to be in seconds for most fixed-income trading.

Many OMS offerings are legacy systems that were built in a time when millisecond granularity wasn’t something that was even considered

Jay Hinton, Charles River

Aladdin also typically displays execution times in front-end applications by rounding to the second. In Aladdin’s case, the time is not rounded if the OMS receives executions back from EMSs that record times in milliseconds.

BlackRock and Bloomberg declined to provide an official comment for this article.

Jay Hinton, senior product manager at order- and execution-management systems provider Charles River, is aware some OMSs may round timestamps up to the nearest second, but states it is not an issue for his firm’s offerings, as all of the orders in its multi-asset system have millisecond-level timestamps.

He says: “Many OMS offerings are legacy systems that were built in a time when millisecond granularity wasn’t something that was even considered. It’s a problem for a lot of systems. We’ve done a fair bit of work to make sure it’s not a problem for us.”

Fix Trading Community – the body that governs the messaging standard – recognises the problem.

Hanno Klein, senior standards adviser at consultant FIXdom and co-chair of Fix’s global technical committee, says: “It may be an idea for a working group to come together to resolve the issue between different EMS and OMS timestamp granularities. There may be a need to standardise on a common granularity and define rules for how to round timestamps for consistent reporting.”

It may be an idea for a working group to come together to resolve the issue between different EMS and OMS timestamp granularities

Hanno Klein, FIXdom/Fix

That need is driven partly by best execution policies – often defined as an attempt to transact at the most favourable possible price – and partly by a lingering distrust of FX dealers on the buy side, caused when several large dealers in the spot market were involved in frontrunning scandals.

The scandals focused continuing attention on dealer behaviour during the milliseconds-long ‘last look’ window, which opens once a client order has been received. Some banks use that period to pre-hedge incoming client trades – indistinguishable from front-running in some cases – or to reject trades if the market moves in a client’s favour prior to execution.

Principle 36 of the FX Global Code of Conduct, written following the scandals, states that market participants should apply “sufficiently granular and consistent timestamping”.

Here’s how that information could be used: first, says Xavier Porterfield, head of research at New Change FX, buy-side firms would be able to keep tabs on what happens to their orders when they click on a price in their EMS and an order message is sent to the market-maker.

In sequence, the market-maker would receive the order and open a ‘hold window’, at the end of which it would check to see whether and how far the market price had moved away from the original quote. If any move was within the dealer’s tolerance, then the order would be accepted and a confirmation returned to the client; if not, a reject message would be sent instead.

The longer the hold window, the greater the chance of the market moving and the order being rejected. Some dealers state they apply holds of different lengths to different clients, depending on their experience with that client. Others will reject trades if the market moves against them, but execute if it moves against the client. Unless the messages are timestamped to the millisecond, it becomes impossible for a client to know how they were treated.

“Does the hold window open 100 milliseconds, 200 milliseconds or 300 milliseconds after the order has left the client’s EMS? This lack of granularity creates optionality in FX pricing and the payoff is asymmetric,” Porterfield says.

There are other TCA use cases, too. A buy-side firm could compare the price at which its order was filled with the market mid-price at the time its order was submitted, for example. Or it could look for evidence of market impact – the possibility that an order might be handled clumsily or pre-hedged, causing prices to move against the client.

All of this analysis would be obscured if an investor was working in whole seconds – or distorted if it was using the wrong timestamps.

Stamp collecting

The latter problem arises from the plethora of stamps available. There are around 3,000 tags – data fields that describe an element of a trade – in the Fix protocol, of which 26 are timestamps.

Separate timestamps exist, for example, to capture the time of execution, broker receipt, desk receipt if a trade is passed between different desks, order-book entry time, or when a transaction is first published to the market, submitted for confirmation or sent to clearing.

Tag 60, the transaction time, is probably best suited for TCA, although other tags may inadvertently get used. Tag 52, for example, is the ‘last sent’ time, which is updated whenever it is passed between an OMS and EMS. Tag 122, meanwhile, represents the original sending time of a trade.

Because tag 52 is often changed as it is passed between systems, New Change FX’s Woolmer says clients using this tag for TCA can end up with a timestamp that lags the actual execution time.

FIXdom’s Klein acknowledges the issue. He says timestamps such as tag 52 and 122 are part of the standard header of a Fix message – used for communication on a technical level between Fix engines – and not intended for reflecting “business events”. Instead, he says, tag 60, the transaction time, is the key timestamp for the purpose of establishing a business event such as the time of execution, and is expressed in the body of a message.

Clients that do TCA need to be especially careful when they look at their data source and its suitability for TCA

Stephan von Massenbach, Modular FX Services

“I’m pretty sure that sending time tag 52 is being used in the industry to pass information as part of the application level of trades, but that is not the intention of it,” says Klein. “I’m also pretty sure that all the timestamps provided back and forth between counterparties would benefit from defining where they are taken. For example, is a timestamp taken when a trade hits an exchange gateway or when it hits a matching engine?”

Modular’s von Massenbach has seen timestamps taken from clients’ own risk or position-keeping systems that are out of sync with the market and make TCA difficult. He recommends getting execution logs direct from an EMS, adding that such systems might not make all the information readily available.

He says: “You might get the confirmation time rather than the actual execution time, and the only way to access the correct information is by a dedicated request. The difference could be as much as half a second, if not a second or two. And if it’s then sent back to the OMS and rounded to the nearest second it introduces a lot of noise into your analysis. That makes life difficult.”

“I think the message is that clients that do TCA need to be especially careful when they look at their data source and its suitability for TCA,” von Massenbach sums up.

Issues with using the correct timestamps are said by TCA experts to be more common among smaller asset managers.

For the record

Buy-side firms don’t have complete control over the process though. Venues, software providers, counterparties and even custodians have a part to play.

Beverley Doherty, global head of FX Connect, says the venue offers a timestamp report to clients, although “we didn’t add everything to the straight-through-processing export because some OMSs can’t consume it all”.

360T group chief executive Carlo Kölzer, says his platform has “really ultra-precision measurement of timestamping and at what stage the message is”.

As with FX Connect’s Doherty, he warns precise data can be trashed by a crude OMS: “If we deliver messages to the API that feeds the OMS, from then on it’s obviously out of our control. The capability of the OMSs is what they are, and we deliver in the best and most precise format. What the OMSs are capable of doing we cannot influence.”

At Quod Financial, chief technology officer Mickael Rouillere, whose multi-asset platform caters to liquidity takers on the buy side, says the timestamps it generates are to the microsecond – or millionth of a second.

But he agrees not all counterparties can be relied on to timestamp with the same granularity or even use the correct Fix tag: “When you’re dealing with TCA, you want to have the timestamp of the creation of the actual transaction. But sometimes it is actually very difficult to understand which one’s which. There are different timestamps in the Fix messages, but you can’t always guarantee that the sender of these Fix messages has been using the right tag.”

Rouillere says the buy side is increasingly becoming aware of the need for more accurate timestamps: “Hedge funds and quantitative funds are asking the most.”

Take it to the bank

New Change FX’s Woolmer adds that asset managers may need to address the issue, not only with their OMS providers but also with third parties such as custodians, if they are given responsibility for collecting data on behalf of asset managers.

He adds: “If an asset manager doesn’t know when a transaction took place on their behalf in the market, then that gap can be costly, especially when we’re talking about algos. That means they could be using venues that have high market impact and may do things in the last look window they wouldn’t want.”

This year, FX Week sister site Risk.net analysed disclosures from the top 50 liquidity providers, including non-banks, on their last look policies. It found that while most firms adhere to the FX Global Code, a quarter have no public disclosures on their last look practices, nor would they share them. More than half refused to publicly state or confirm their approach to hold times.

So, what can buy-side firms do?

Going direct to the source for timestamp data is the route advised by Tradefeedr. It is building an industrywide data utility that relies on banks and trading platforms making their data available for independent analysis, hoping to optimise interaction between FX market participants.

Balraj Bassi, co-founder of the analytics start-up, says: “I think they should take the timestamp from the banks. If I’m trading with a bank, I need to be talking to the bank directly. How old is the quote I’m trading on? If it’s very old I need to go to talk to my platform provider and ask ‘why am I trading on old prices from banks?’”

“The next thing I want to know is how long the bank held it for. So there’s two things you can get from banks: the quote age and the hold time. The other thing on the buy side, which their platform should have, is a response time of when I sent it and when I got a receipt back. All three, in my opinion, are important,” he says.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact customer services - www.fx-markets.com/static/contact-us, or view our subscription options here: https://subscriptions.fx-markets.com/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact customer services - www.fx-markets.com/static/contact-us to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@fx-markets.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. Printing this content is for the sole use of the Authorised User (named subscriber), as outlined in our terms and conditions - https://www.infopro-insight.com/terms-conditions/insight-subscriptions/

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@fx-markets.com

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. Copying this content is for the sole use of the Authorised User (named subscriber), as outlined in our terms and conditions - https://www.infopro-insight.com/terms-conditions/insight-subscriptions/

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@fx-markets.com

More on Risk Management

Four more banks join CLSNet

Bilateral payments netting service using distributed ledger tech now has nine firms live

Investment Association calls for standardisation of FX reject codes

The 13 new high-level categories will allow rejection causes to be remedied quicker

FX HedgePool goes live with three buy-side firms

Two US buy-siders trade with European firm on peer-to-peer utility created for them to source liquidity from each other

BIS calls for wider adoption of FX Global Code

Yet some industry participants question the benefits of asset managers signing up to the voluntary principles-based document

Refinitiv pledges FX brokerage to Australian bushfire relief

The area already burned is triple the size of the land destroyed by the 2018 California fires

Morgan Stanley more than doubles Q4 Ficc revenues

All US banks see Ficc revenues improve substantially in Q4 versus a year ago

Colombia culls external reserve manager to boost competition

From 2016–18, the central bank reduced the number of institutions from seven to six

Cboe plans comeback in crypto markets

US exchange plans to offer crypto derivatives after previous attempts at regulatory approval to list crypto ETFs thwarted